Fair warning: This post is a long one, since I had to completely rewrite the book twice. Buckle up.

One of the most common suggestions to people who want to run CoT is that they run the books out of order. Since books one, two, and three focus on stopping the shadow beasts, it only makes sense to continue with that thread rather than take a break for a different adventure.

That said, Book Five took quite a bit of reworking before I felt like it was usable. Besides scaling down, some events had to be removed, and a lot of blanks had to be filled in.

Book Five is also like Book Three in that it’s totally possible to take on the end game right after the first session, skipping over the middle part of the AP. If you’re someone who does Just In Time Prep, you’ve been warned.

What I changed (Part One)

Oh, quite a bit. For pretty much the whole book, I figured out what the absolutely vital piece of information / action for each scene was and then re-wrote everything. I knew I had to hit certain beats, so I focused on those:

- Finding out about House Drovange and the Council of Thieves from an insider

- Getting some sort of introduction to the Mother of Flies

- Rescuing the Mother of Flies so the party can learn about Walcourt

- Taking on Walcourt so the party can kill Ilnerick and create / destroy the Aohl

Re-ordering AP events

Due to swapping books four and five, this meant that the fall of the mayor and Senior Drovange couldn’t have happened yet. Therefore, I had to remove any reference to riots or chaos and save those events until after Ilnerick is take care of. Oddly enough, this wasn’t that hard, since most of the book ignores the events in the Crown Sector.

The Kick-Off

The inciting incident involves dealing with a ‘trusted’ new NPC who the players have never met. My group leans towards paranoia, so the chances of them biting were slim. Instead, I pulled out what absolutely had to be introduced with that scene:

- Confirmation that Ilnerick is in Westcrown

- Some information about house Drovage (including their involvement with the Council of Thieves)

- The involvement of the hags in whatever went down when Eccardian was born

- The fact that there’s a splinter faction within the CoT

Rather than a new NPC, I used the interlude with the Children of Westcrown to deliver an alchemist to the heroes for questioning. Rugo is a bastard son of Senior Drovage, kept around because he’s utterly loyal, fairly useful, and good to have in case the house is left completely without heirs. With some threatening, he should reveal everything the players need to know in order to move on with the plot.

Mother of Flies

In the book, the players are ambushed while seeking out someone the contact knows, and a follower of the Mother of Flies steps in to help. Instead, I decided to condense things a bit, making the scene where the heroes interrogate Rugo the same scene as the ambush.

To make this work, I moved The Mother of Flies from the Hagwoods to the sewer, reworking her backstory. After her sisters were killed, she fled, but has made her way to the city, hoping to take revenge on the Drovenge family. Unfortunately, her lair was discovered and she’s currently under siege by the Council. At the moment, she’s holding them off, but every day they lose ground.

Some of her agents are still free, and have taken to roaming the sewers, killing reinforcements when they can and looking for a chance to break the siege from the other side.

So, I have two moving parts in the sewers now: Siege reinforcements and Mother allies. As soon as I’m done with the PCs interrogating Rugo, they’re stumbled upon by the reinforcements. As soon as that ruckus is underway, the Mother’s allies come to see what’s going on. After helping out with the combat, the allies can offer some information about the Mother of Flies:

- She was chased out of the Hagwoods after her counterparts (Sister and Daughter) were killed

- She came to town to enact her revenge

- The CoT figured out she was around and have her under siege

- Rugo was a part of the massacre and was a target for the Mother. The allies that are behind enemy lines are there because they were doing reconnaissance

The main ally is the from the book (Dog’s Tongue), and will give out enough information to hook the players into at least checking out the Mother of Flies.

If the players help end the siege (which is likely, since the siege is also going to make getting around in the sewers harder if they ignore it), they find out where Walcourt is, the history behind Drovage and the Mother of Flies agrees to hole up away from them and leave town once they enact her revenge for her. After that, the players are free to plan an assault on

And then things went to hell

A good plan never survives contact with the players, but I hadn’t expected them to completely wreck them before we even got to the first session.

I was in the middle of planning Book Five when the players finished Book Three. After clearing out Delvehaven, the players decided to resurrect one of the vampires. She was previously a vampire hunter, so likely to be good or neutral, and probably had information they needed. This obliterated the need for half of next book.

I was weirdly delighted with this turn of events. I was losing an interesting NPC (Ailyn, the Pathfinder Bard) soon, so this would give me someone new to introduce the story. Also, it felt a bit more elegant, since even with reworking, the siege felt awkward. Still, it required some scraping of my plans and figuring out if they even needed to deal with the titular Mother of Flies. After all, they’d have the plans for Walcourt and hints about Drovage being involved with the Council of Thieves. They’d be missing some backstory, but that could be inserted later.

What I changed (Part Two)

I decided to create four plots for this book:

- Reviving Vahnwynne (and dealing with the fallout)

- Potentially dealing with the Mother of Flies

- Doing a favor for the temple of Calistria

- Taking on Walcourt

Reviving a slayer

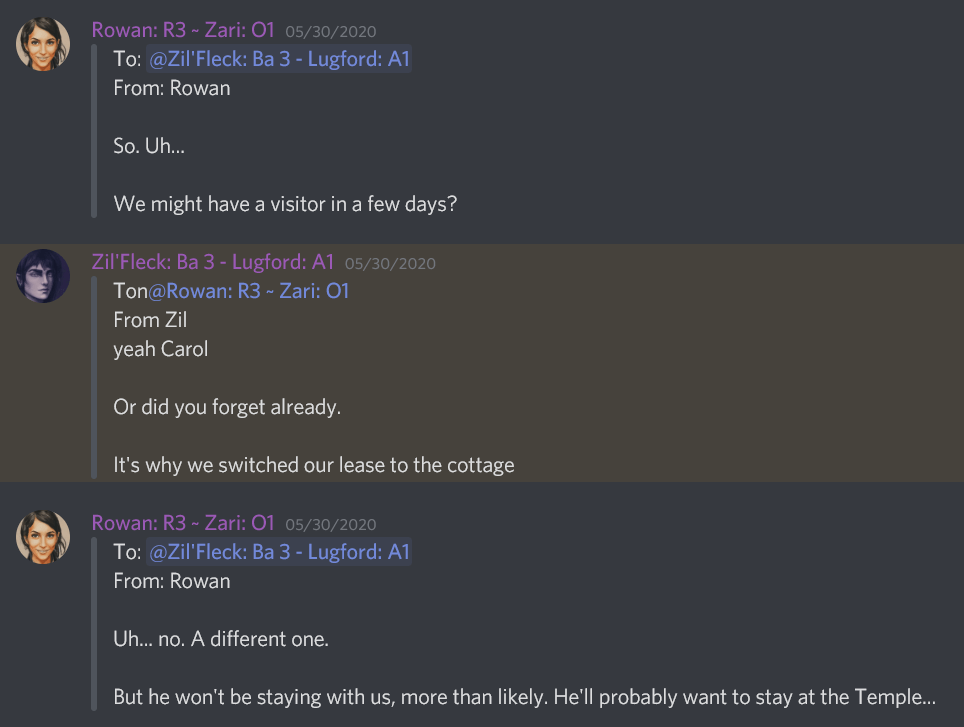

Reviving Vahnwynne comes with three complications: Finding someone to do the resurrection, acquiring a diamond worth 10k, and dealing with the fallout.

As I wrote before, the Temple of Calistria is the only game in town when it comes to doing a non-evil resurrection. The Temple won’t simply take payment for their services (in fact, they’ll refuse it). Instead, they’ll require a favor. They won’t force the players to carry it out before the resurrection, but when they come calling, they’ll most certainly have a window in which to get it done.

Acquiring a diamond is less of an issue, especially since one of the Children of Westcrown happens to be the daughter of a prominent jewelry merchant. The biggest problem there is finding the cash, since much of the previous spoils have gone into buying property or outfitting the rest of the rebels.

Finally, the fallout. I’ll write about this more in another post, but in short, Vahnwynne comes back with emotional scars. She was a CG person who was forced, via the nature of vampirism, to commit evil acts. Coming back, the memories of such events stay with her, haunting her days and nights. It also doesn’t help that she’s brought back by a group of strangers. If they want her help, the PCs will have to invest some time in getting to know her (and her issues) and helping her recover.

The Mother of Flies

With the resurrection of Vahnwynne, the Mother of Flies becomes unnecessary when it comes to pushing the plot forward. She has some interesting information about the backstory of the Drovage family, but that’s about it.

Rather than use her as an arbitrary stumbling block, I decided to make her optional. I also opted to place her in the sewers of Westcrown (as suggested in a Paizo forum thread) in order to tighten up the plot. She fled from the Hagwoods with a band of followers and has resettled in forgotten part of the sewers, plotting her revenge against Drovage. At the time of the AP, she’s been discovered and is currently under siege.

Vitti, the rebels’ druid, can clue the main PCs in on her existence. In my game, he’s been mapping the sewers, and would note that there’s some strange activity going on. The usual signs of life are disappearing and they’re running into more groups of humans. The players can opt to follow this thread if they want, with the reward being information and a possible alliance, either against Walcourt or for one of their more long-term goals. It also doesn’t hurt that a victory would mean taking out a good chunk of the Council of Thieves standing forces.

I also changed the hook, since the players rarely use the sewers to go anywhere. Instead, two of the CoW (Vitti and Larko, for my game), barely escape an encounter with a band of Council thugs. They tell the PCs what happened and leave it up to them what to do next: Investigate, delay, or ignore the threat.

The Siege

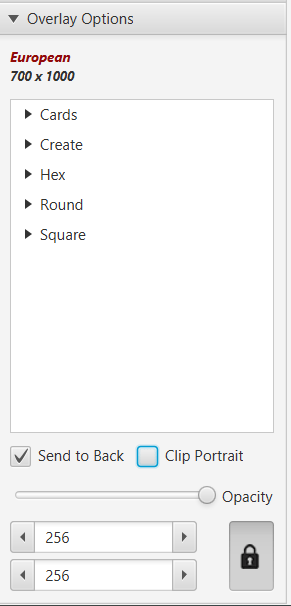

Moving the Mother of Flies underground meant I had to redo the siege. The book lays it out as a rather linear experience involving a lot of enemy fey, which doesn’t make a lot of sense, so I redid it to make it feel more like a group of people being penned in.

The center of the siege is the Mother’s hut, which she placed at a very specific point in order to draw on its power. There are three open areas around her hut, which were originally intended as space for their camp to grown. The Council’s thugs now occupy those spaces, however, blocking her and hers in.

The thugs, at this point, have tried a few pushes, but quickly found that the Mother’s crew can do some serious damage to them. Mother’s side, however, has found that they can’t make a move without the two other sides falling upon their back line. Even if they coordinate with Dog’s Tooth’s group, it still leaves them vulnerable. Both sides are at an impasse.

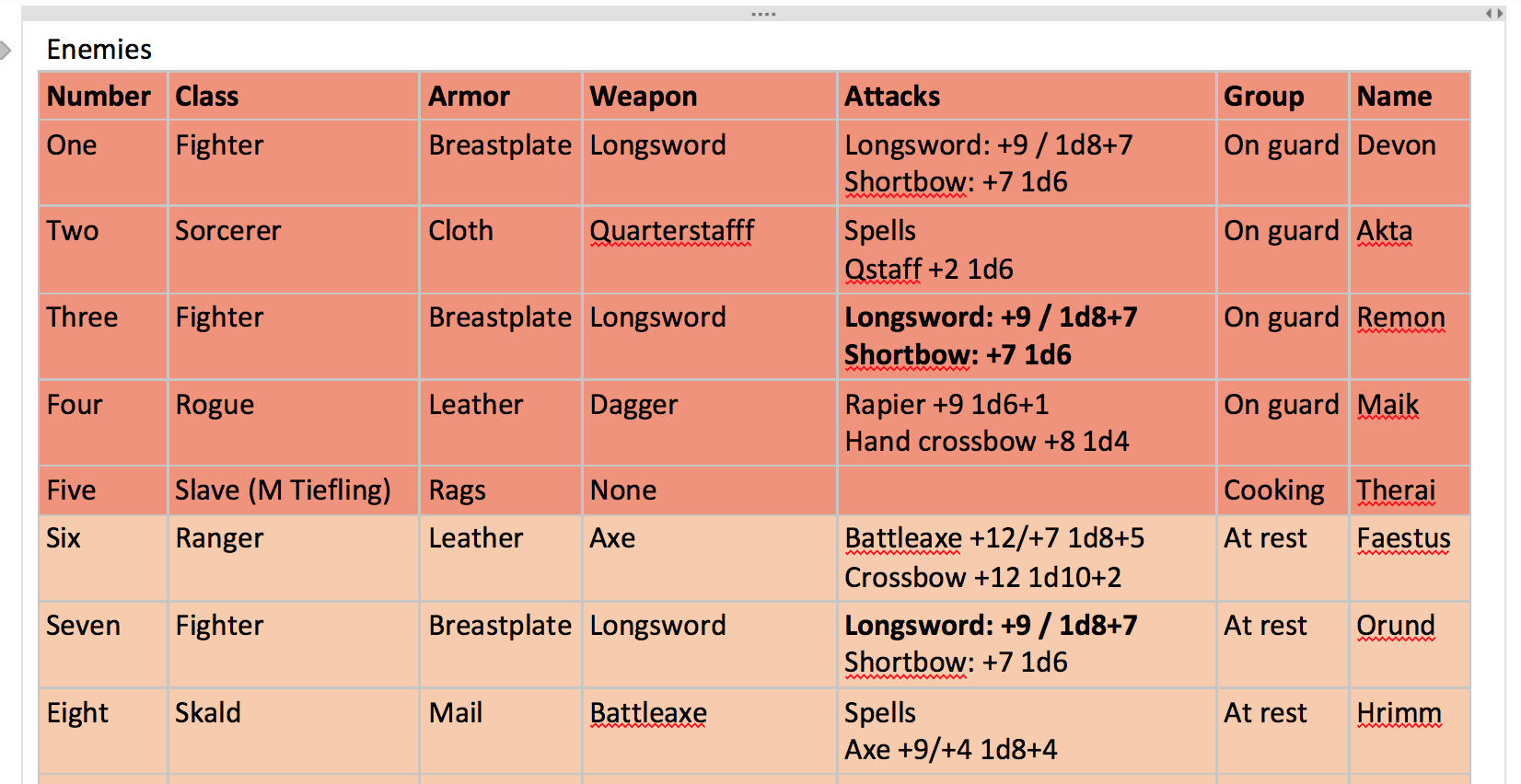

Each side has about 15 people in it, though several of those people are slaves (something the fey don’t recognize as different than any other enemy). Each group is comprised of one lower level magic caster, one lower level priest, a mix of fighters and rogues, a ranger, and a skald / bard / some other force multiplier. The highest level enemies will be whoever escaped from the fight in the sewers.

Calistria

I’ll be detailing this subplot in another post, but the short version is that the players are tasked with recovering the body of a murdered temple priestess and punishing those responsible in whatever manner seems fit. This will take the crew out of town to a manor, allowing for a nice change in scenery and a chance to use some of their more esoteric skills.

Walcourt

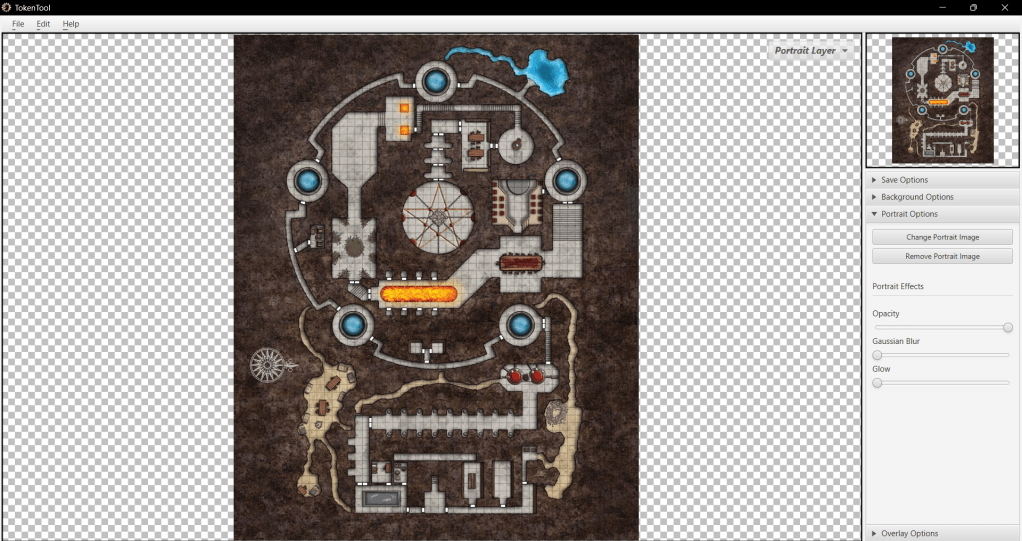

I wasn’t a huge fan of Walcourt as it was in the book. It looks like a fun romp… for any other game. The tone of my game had gotten a bit grim, so I decided to remove some of the goofier elements and play up the corruption of Ilnerick. Rather than being a standard hive, I fashioned it to mimic a Pathfinder lodge, specifically, Delvehaven. The motifs and decor will be familiar to the PCs, and some of the vampires will be former Pathfinders who were tempted too close to his lair.

I ended up using the wonderful Village to Pillage: Murder Mansion as my map. I left most of the levels furnished, only bothering to customize the basement. In game, Walcourt formerly belonged to a noble house that fell during the Chelish civil war. The manor and its lands have never been rehabilitated, in spite of the fact that it sits in the middle Crown Sector. The official reason for this is that the matter of ownership is unclear since many houses could possibly lay claim to the land and the house, but the leaders of Westcrown have made it clear that whoever claims the land must also pay the back taxes on it. Unofficially, Walcourt is kept empty so that the Council of Thieves has a secure location on the island.

Also, you have to keep your pet vampire somewhere, right?

How did it go?

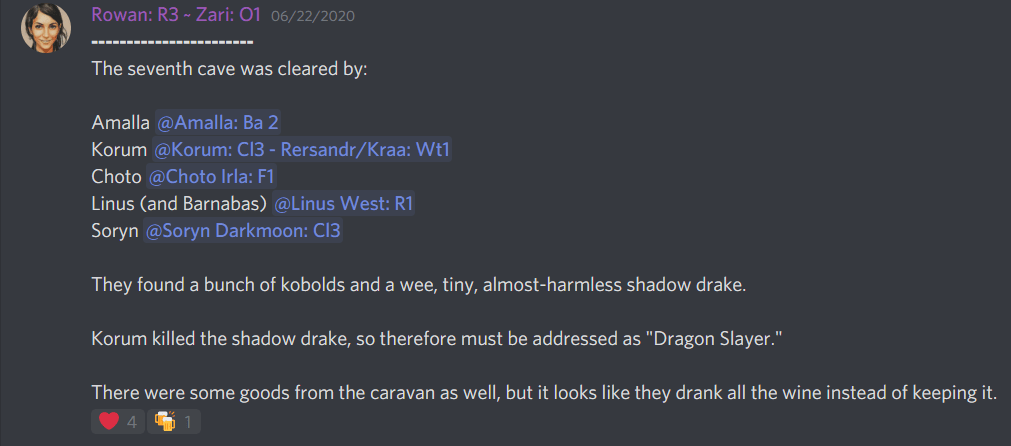

The kick off

Session one was basically set-up for the entire book, What Lies in Dust style. The players got all the hooks during this session and were given no particular order in which to do them. Vahnwynne was raised, they found out about something going on in the sewers, the deal with the temple of Calistria was struck, and they learned the location of Walcourt.

The players immediately accepted that their newly risen party member was traumatized and set about ways to alleviate it. They dug deep into their various tricks to find spells, skills, concoctions, and treasure to figure out ways to help her, which is always nice to see as a GM.

Dropping all the hooks on them at once also seemed to work well, since it gave them freedom to prioritize. The book is very linear, so I’m glad I reworked the plot so that they’re not dependent on each other.

The sewers, the fey, and the siege

The players decided to go into the sewers first, reasoning that if the sewers were now off-limits, the CoW were going to have a harder time getting around.

I set up a crew of Council reinforcements for them to stumble upon. I made it a CR 13 encounter, figuring I’d let the players get into a dangerous situation and then have the red cap Dog’s Tooth step in. He could help turn the tide and get the players moving on the Mother of Flies plot.

One misstep I made: I underestimated my players. They actually did fairly well against the reinforcements, even if the encounter was running long. I had meant to get them to the fey hideout this session, but I ended up having to stop right after introducing Dog’s Tooth.

Meeting the fey

In the third session, the group met Dog’s Tooth and his camp, and it confirmed my suspicions: If the PCs started with common ground with the fey, they’d have no problem making a deal with them. They figured out that many of the fey in the camp were evil, but knowing from the start that they had a common enemy and that the fey intended to leave town after their revenge was had, they decided to play ball.

The PCs got some rough details from Dog’s Tooth about the siege, letting them know that the battlefield had three areas, and that each one held ten to fifteen mortals. This was where I ran into a small problem.

If you give your players some rebels…

…They’ll want to bring the rebels to the fight.

After hearing about the number of potential combatants, the players immediately started planning on bringing all of the Children of Westcrown with them. All of them. I choked at first, since that meant I’d have fourteen friendly NPCs to control.

I almost said no, but then I decided to think about it. After some discussion with my husband (who’s also one of my players), I worked up a solution that would, hopefully, keep combat moving and keep me from having to control an absurd amount of mobs.

The system ended up working quite well. The combat never got bogged down, and while it was still a long fight (around two hours), it never felt slow or drawn out.

The fallout

The players were happy that they were able to clear out a chunk of the Council and got to learn a bit more about the Drovage family. They were also interested in forging an alliance with the fey, though I decided to delay that a bit. The fey informed the players that they had to relocate, and that they would be in contact once that was done.

The players also decided to take a few prisoners from the siege so that they could find out where the other hideouts for the CoT were… which involved maps I totally did not have. Between sessions, I threw together a few possible encounters: A main gathering place for the CoT thugs, a tavern just outside of town (used as a secret entrance to the city), and a warehouse in the docks (mostly for smuggling goods into and out of the city).

Calistria

I had major worried about this side-quest, since there was a chance that the players could seriously foul it up. I decided to heed the advice of Matt Colville, though, and not worry about how the players would get themselves out of a jam.

In the end, the players did perfectly fine: They got out with everything they needed and even made few new allies along the way. It was also a nice break from a combat-heavy book.

The warrens

In the end, the only place that the players ended up hitting up was the Warrens. Once again, I grabbed one of the awesome Village to Pillage maps, tossed in a ton of NPCs, and let the players go nuts. They captured a few guild members, allowing me to toss some more information at them.

The most important discovery was a coded note with instructions to watch certain people. While the players were able to decode the text portions of it, the names of the actual people were left as a mystery. They did manage to get a few names out of the captured thieves, but they didn’t manage to grab the ones who would have been able to tell them that they, the PCs, were on that list.

This was fully intentional, as I wanted to make the players a tiny bit paranoid without sending them into a frenzy of self-defense. Sometimes, a GM needs to be a bit evil, okay?

Delvehaven

Finally, after getting their insider (resurrected Vahnwynne) better and raising some hell, the group descended upon Delvehaven.

Honestly, while this encounter looked super tough on paper, the group breezed through it. They used their insider knowledge, planned the heck out of what they were going to do, and brought all the higher level people with them. Illnerick never stood a chance.

If I could do it again…

Looking back, I’m not sure I’d change a thing. I liked how the book played out, I figured out how to run large-ish combats, and the players seemed to enjoy themselves.

One thing that did bug me: Downtime. With this book, I offered a ton of downtime, spreading out the major events over months. There was nothing especially pressing. Even the request from Calistria didn’t have a due date (as long as they didn’t put it off too long). This lead to the number of sessions doubling, which wasn’t a bad thing, per se, but caused the tension to ease up a bit too much.

I decided that was fine, though. After all, it just made removing all downtime in the next book more distressing…