In my current Pathfinder game, the players have access to a crew of lower-level rebels. Normally, these rebels are doing their own thing, helping save the world in the background, only coming forward for bits of role play or when one of their areas of expertise are needed. Since they lag quite a bit behind the PCs, they’re rarely taken on missions.

That is, until the latest mission came up.

The PCs were asked to break a siege. They would take one side of the siege, while another group would take another, and those within would take out the last section. They were warned that each side of the siege consisted of somewhere between ten to fifteen people.

As soon as they heard those numbers, they told me that they were going to take the rebels.

“Which ones?”

“All of them.”

I nearly balked, because that would mean controlling not only 15 enemies, but thirteen friendly NPCs. I could see the logic in their demand, though: Of course they would bring more people to the fight. Sheer numbers and a bit of strategy would likely keep the lower level NPCs safe, whereas going on their own, they would be taking a much larger risk.

So, I set about trying to figure out how I would deal with this combat without it becoming a slog, and without it breaking my brain.

A small large combat

Pathfinder does have rules for large scale combats, but those tend towards dealing with actual armies. The scale of this battle was way too small for that to work, so I decided to roll my own.

Organizing the players

I declared all of the “leaders” of the combat: The PCs, my GMPC, and an NPC that they had been fighting alongside recently. Each leader would be commanding a team. If someone wasn’t a leader, then they had to be on a team.

I made my life a bit easier by putting my GMPC in charge of the team of healers and the NPC in charge of just one person, and only so she could get flanking. That minimized the number of decisions I had to make during combat, since one had a set job, and the healers (hopefully) would have actions that were fairly obvious.

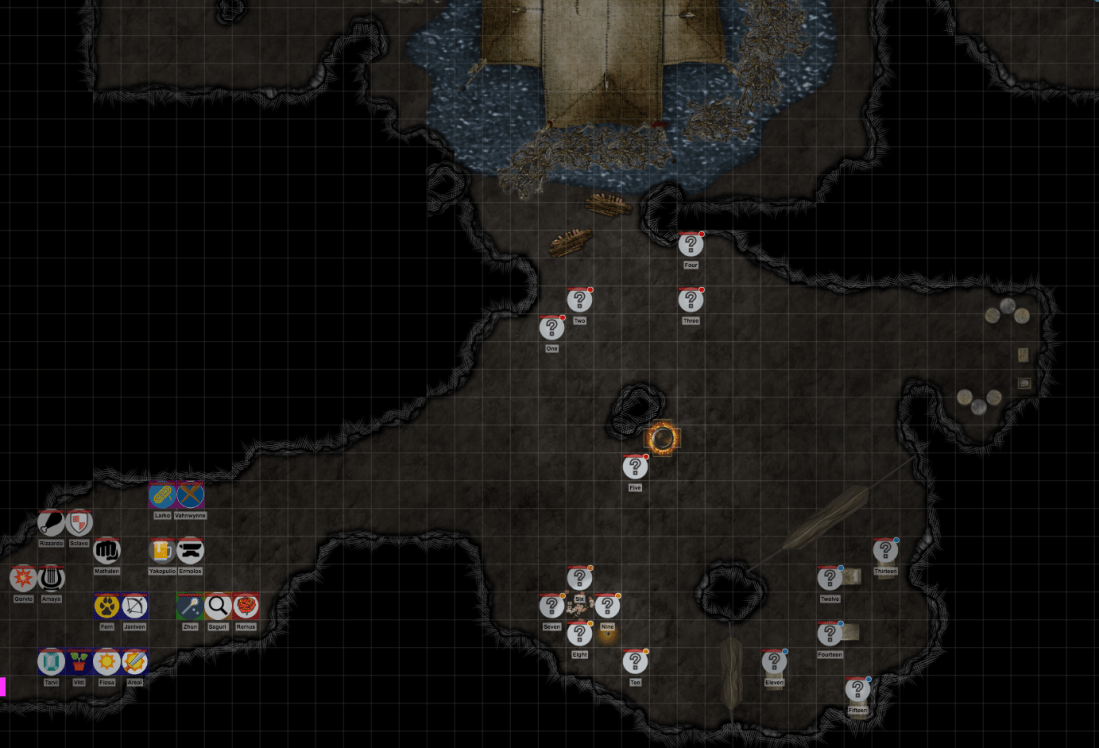

Once I had those lower level rebels claimed, I opened up the rest of them to the PCs. I set up a page on Roll20 with all of the tokens for the rebels and let them dole them out among themselves.

This relieved me of having to control a ton of rebels, but I was still worried that combat might take forever as each player looked over an unfamiliar character sheet and tried to sort out what they could do. This can sometimes be a problem in the interludes, when the players have complete control of a rebel (which is why they tend to keep picking the same ones and leaving the unfamiliar ones for me to control). The rebels are level four, so they’ve acquired more than a few tricks.

In the interest of time, I decided that the leaders wouldn’t have absolute control over their team. Instead, at the end of their turn, they could do one of two things: Give a general command to the team (“Take out the cleric!”) or a specific command to one team member (“Cast web over there!”). Otherwise, the characters would either keep on doing what they were last asked to do or do something that made sense to them.

On the last point, I tried to be clear: The rebels may not act in a way that was the most tactically advantageous. They have their own biases, including friendships, romantic leanings, rivalries, personal vendettas, and fears. They won’t be complete idiots, but they may give up a flanking opportunity in order to protect a friend. They’ll follow orders, but they’re not trained soldiers. They’re used to acting in small groups and watching each others backs.

This simplified things much more for me: I didn’t have to worry about as many decisions, and I could give each rebel some basic strategies that relieved me from looking over their character sheet each turn. I did tell the players that the leaders could communicate freely (“I could use a heal / web over here!”), but at the end of the day, they decided what to do with their people on their turn.

Finally, I grouped the teams to always go after their leader rather than track a bunch of initiatives, because that way lies madness.

Organizing myself

Now that I had the players and rebels sorted, I moved my attention to the enemies.

Pulling back the curtain, the actual combatants weren’t as high level as the players probably expected. They consisted of some lower level fighters, rogues, and casters and a higher level skald and ranger, as well as three non-combatants (slaves who were brought with them in order to do basic scut work). Still, I needed to have my ducks in a row.

I decided to split them into three groups: On watch, at rest, and sleeping. Each group would share an initiative, with the on watch group having a +8, the resting group having a +4, and the sleeping group having a +0. On their turn, they’d act however it made sense, because I didn’t feel like keeping track of sub-initiatives.

I also made a cheat sheet for myself, including their default strategies, gear, and attacks. I wanted to pull up their sheets as little as possible. As much as I love Hero Lab, the interface can be a bit much if you’re juggling more than a few characters.

Organizing Roll20

Normally, I tracked hit points and conditions through Hero Lab, but for this combat, I decided that going to be too slow. Instead, I used the bar and icon features for tokens, letting me keep track much more easily. I also popped their AC on one of the bars so, once again, I didn’t have to look at sheets.

Rather than trying to remember who was on what team, I used the aura feature of Roll20 to make it clear who was answering to who. I set the aura radius to 0 and square, and gave each team a color that matched their leader. Because my tokens are round, this allowed the aura to show without overtaking any other squares.

I also tracked the initiative openly. Normally, I keep the initiative to myself, but in this case, I felt a bit of meta-gaming would make everything move along a bit faster.

How’d it go?

While I wouldn’t call the encounter short by any means (it ran for at least two hours), it was way more efficient than I’d expected, and there was less fatigue than there normally is in longer combats. The players stayed engaged, and at the end of it gave it a thumbs up.

The players adapted to controlling a team quickly, using them to control the field of battle and give themselves advantage. While the rebels had trouble hitting very hard, they were more than capable when it came to flanking, pinning down, or tossing out spells.

While the combat lasted a while, eventually the group completely wiped the board. They took down most of the enemies and got the last few to surrender once it became clear that they were not only going to lose, but that escape was impossible. None of the rebels were lost, or even significantly hurt. And, best of all, I didn’t feel like my mind was made of mush.

What would I do next time?

While I was largely satisfied with how the combat ran, there were a few tweaks I’d likely make to my prep.

The one thing that had me going back to my sheets were saves. A web was laid down, so I had to keep rolling to see if the mobs were able to free themselves, which meant a ton of going back and forth on their turns.

I’d also make sure players could see all of the health bars. I could see them, but I forgot until too late that the players couldn’t. While some might see this sort of information as meta-gamey, it might have sped up combat a bit rather than have players ask about the health of their team.

I would also have sorted out a macro to deal with bardic songs. Changing a bunch of AC / to hit bonuses at once is a pain and a half. I guess it’s time to do a deep dive into the Roll20 API!

I really like this idea for mass combat. I’m never comfortable with the “mob rules” type approaches, and this is a good way to find middle ground and get that individual granularity without bogging yourself down too much in scutwork. Organization is crucial.

LikeLike